|

The Setting |

|

|

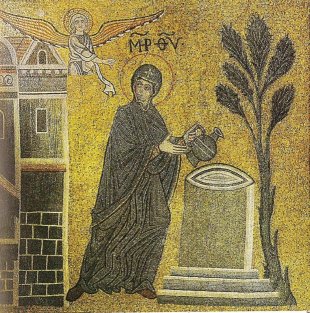

The Well |

|

|

|

|

|

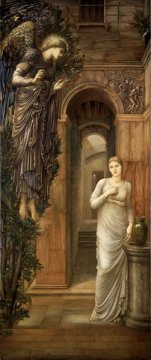

Occasionally a

fountain was substituted for a well. Interestingly, the image of the well was revived by Pre-Raphaelite painters such as Rossetti and Burne-Jones. (Below). |

|

|

|

|

|

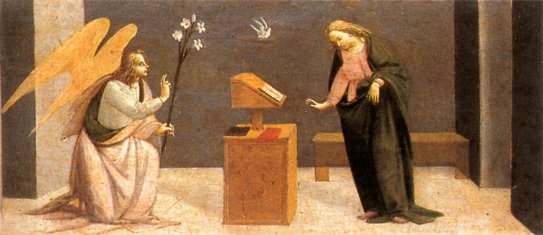

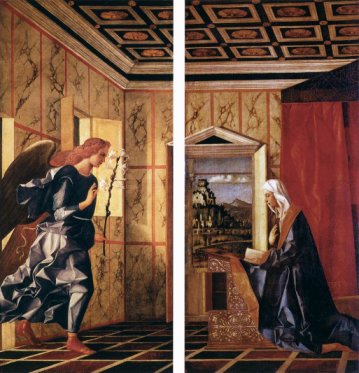

A simple room The most familiar setting for the Annunciation is indoors. As befits the Virgin, the room should be simple, as in this image by Bartolomeo di Giovanni. However, simplicity is not necessarily appealing to artists. In this image by Giovanni Bellini the room is simple enough, but the decor is far from it. Frequently, the room was represented by a loggia or portico; Annunciation paintings for nunneries were often set in cloisters. |

|

|

|

|

|

The indoor room provided an infinite range of possibilities; Flemish artists frequently employed homely, domestic settings such as in this painting by Roger Campin. Here, Mary seems much too engrossed in her book to be troubled by annoying angels that drop in unannounced. |

|

|

|

|

|

The indoor setting doesn't necessarily contradict the story of the well; the protoevangelium tells us that Mary rushed indoors in dismay when she heard the (invisible) angel, whereupon Gabriel came in and revealed himself. Barbara G. Lane (The Altar and the Altarpiece, Sacramental Themes in Early Netherlandish Painting) feels that it isn't domestic at all, but a church sanctuary, and certainly the architecture has ecclesiastical elements. The stained glass family coats of arms suggest a house though. I have no problem with the picture illustrating both the church and domestic motherhood; sometimes I feel that today's scholars are obsessed with looking for precise interpretations in ways that would never had occurred to the original artists or patrons. |

|

|

In a church The depiction of Mary inside a church, especially a Gothic one as in this wonderful painting by van Eyck, seems an odd idea. This setting, though, underlines the importance of the Virgin to the church, and echoes the early stories of Mary working in the Temple. |

|

|

|

|

|

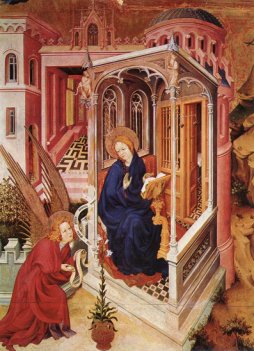

This painting by Melchior Broederlam shows two different church-like buildings; the front part is gothic, the rear a classical temple. This arrangement serves to link the Old and New Testaments and the prefiguring of the virgin birth in the Book of Isaiah. (see sources). |

|

|

|

|

|

Exotic settings As suggested above, some artists opted for highly elaborate, even grandiose settings, with complex perspective, using them as vehicles for artistic showing off. This version by Fra Carnevale from Urbino may be a tour de force of perspective, but you wonder how Gabriel ever found his way in. |

|

|

|

|

|

My vote for for most grandiose setting of all comes from Veronese, an artist well noted for grand gestures. |

|

|

|

|

|

Doing without Many later painters did without any recognisable setting, offering just a dark background. In getting rid of what they considered distracting detail they were able to focus on the emotional intensity of the two figures. Back to San Marco I know I've already tried to persuade you to visit the Museo di San Marco in Florence - here's another attempt. Once past the Annunciation fresco at the top of the stairs you will find a series of monks' cells, each with a fresco by Fra Angelico (or assistants). In the one shown below, the wonderfully simple Annunciation is painted as an extension of the cell itself; Mary and Gabriel are there in the room with you. And there in the corner is a real window looking out on to a garden - the enclosed cloisters of the monastery. Who needs complexity? |

|

|

|

|

|

Talking of gardens . . . In many Annunciation images we glimpse a garden through a doorway. A distant gate is often locked, as in this painting by Domenico Veneziano. |

|

|

|

|

|

The enclosed garden image refers to the Song of

Solomon, and symbolises virginity: A garden inclosed is my sister, my spouse; a spring shut up, a fountain sealed. (Ch 4 v 12) The gateway into the garden can be see as representing the Virgin Mary as a means of attaining heaven. |

|

|

|

|