|

The

Legend of the True Cross, 1. |

|

Arezzo is quieter than most of the Italian tourist hotspots, but full of good things, many of which I mention on my Margarito pages. The main draw is the Finding of the True Cross sequence by Piero della Francesca in the Capella Maggiore (Bacci chapel) in the Basilica of San Francesco. To contemporary eyes, it is the visual representation of a rather obscure legend. To the Franciscans of the fifteenth century, it was an integral part of their liturgy and theology. |

|

|

|

|

|

Basilica of San Francesco |

|

The frescos were commissioned by the Bacci family and were painted between 1452 and 1466. The legend depicted tells of the death of Adam, the placing of seeds or a branch of the Tree of Life in Adam's mouth, the cutting down of the tree and its use as a bridge by Solomon, the Queen of Sheba's recognition of its sacred future, its concealment by Solomon, its subsequent rediscovery at the time of the crucifixion, its rediscovery by Saint Helena, and its ultimate return to Jerusalem by Heraclius in 630. I'll fill out the story in detail as we look at the various elements, but it's important to understand that here it is not presented as a chronological narrative - storytelling is the least important element of the artwork. |

|

| Sources of the legend The main source was the Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine. Voragine's account draws on a number of sources: the most important ones are the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus and the Ecclesiastical Histories of Socrates Scholasticus (c 439) and Sozomenus. (c 443). |

|

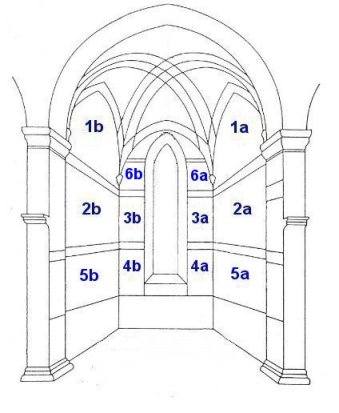

Arrangement of the artwork The frescos are arranged so that linked events face each other on the side walls of the chapel, or are next to each other on opposite sides of the window. The diagram below right is an attempt to make this clear. I've presented the images below to follow Piero's arrangement. What do I mean by linked events? I've tried to explain this in the notes below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1a should be read from right to left. On the right of the picture, Adam lies dying. He points towards the gates of Paradise. He is asking his son Seth, (leaning on a stick), to go there to ask for the oil of mercy to anoint his body. In centre background we can see the second scene. Seth has arrived at the gates, where he meets the Archangel Michael. Michael tells him that Adam will have to wait for more than five thousand years for the oil. Instead, he gives Seth either seeds, or a branch of the Tree of Life, depending on which version of the legend you read. On the left we see the burial of Adam; traditionally this happens at Golgotha, and Adam's skull often appears beneath the cross in crucifixion scenes. Seth places the seeds, or the branch, in Adam's mouth. The tree that grows will ultimately produce the timber used for the crucifixion. The story of the oil is another link with the Passion; Adam finally receives it, and achieves redemption, when Christ descends to Hell. 1b, known as 'The Exultation of the Cross', describes the historical events of 630. The Byzantine Emperor Heraclius, having beaten the Persian King Chosroes, is returning the cross to Jerusalem, stolen from there by Chosroes in 615. This brings the events of the fresco cycle full circle. |

|

|

|

|

| As a straightforward narrative sequence, the two pictures below (3b and 3a) should appear between 2b and 2a, as we'll see below. In 2a The Queen of Sheba discovers the wood of the future Cross and has a vision of its destiny (left). On the right she tells Solomon that his dominion over the Jews would ultimately be destroyed by a man who would die on that beam. This is beautifully matched by 2b, in which another Queen - Helena - discovers the three Crosses in a field outside Jerusalem. Socrates Scholasticus describes the field, and the ruination of Jerusalem, with a beautiful quote from Isaiah: 'And the daughter of Zion is left as a cottage in a vineyard, as a lodge in a garden of cucumbers, as a besieged city. ' (Ch 1 v 8) . On the right we are in the not-so-ruined city of Jerusalem, which looks strangely like Arezzo. The identity of the true cross is verified by holding it over a corpse, which comes back to life. |

|

|

|

|

| 3a follows the events of 2a above, and mirrors the events of 3b, which comes before what happens in 2b above it. In 3a, which is generally considered to be painted by one of Piero's assistants, servants of Solomon are busy burying the wood, in the hope that the Queen of Sheba's prophecy would not come true. 3b shows a rather unedifying episode. Unable to find the cross, Helena hears of a Jew called Judas who knows where it is. She tortures him by leaving him in a pit without food or water. Eventually he gives in. In this fresco he is being hauled out of the hole, in contrast to 3a. |

|

|

|

|

| 4a shows the Emperor Constantine's vision before the battle of Milvian Bridge in 312 against Maxentius. An angel shows him the Cross and tells him 'By this sign shalt thou conquer.' To match 1a this should be Archangel Michael, but there is no evidence for this. A number of commentators suggest that 4b, the Annunciation, is nothing to do with the rest of the cycle, but this is not so. Gabriel's Annunciation to Mary is the beginning of the Christian story; the annunciation to Constantine led to his conversion and ultimately to the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity. There is another link: Mary is regarded in Christian theology as the new Eve. |

|

|

|

|

| 5a shows

Constantine's victory over Maxentius, under the sign of the cross. To a

contemporary viewer, it would have had a further significance: in 1460 Pope

Pius II called for a new crusade against the Ottoman Turks, and there is

more than a hint of this in the image. 5b tells the story of Chosroes and his defeat by Heraclius. In 615 Chosroes had stolen the True Cross from Jerusalem and set it up in the temple dedicated to himself, seen on the right. Below the temple, Chosroes, in the blue cloak, awaits his execution. Following his victory, Heraclius returns the cross to Jerusalem (see 1b above.) It might be pointed out that the most important event in the narrative of the cross, the Crucifixion itself, is not included. A glance at the view of the chapel at the top of the page explains why - the crucifix itself dominates the chapel. |

|