|

Saint

Mark and Venice |

|

|

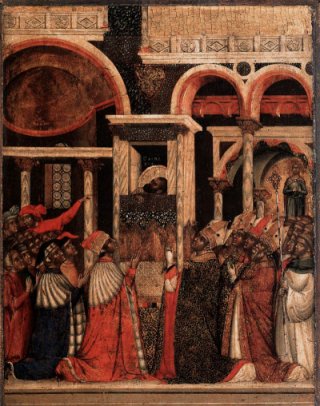

And

it happened in the year of grace four hundred and sixty-six in the time of

Leo the emperor, that the Venetians translated the body of St Mark from

Alexandria to Venice in this manner. There were two merchants of Venice

who did so much, by prayer and

by their gifts, for two priests that kept the body of St Mark, that they

allowed it to be borne secretly to their ship. And as they took it out of

the tomb, there was so sweet an odour throughout all the city of

Alexandria that all the people marvelled, though they did not know where

it came from. Then the merchants brought it to the ship, and after setting

sail, let other sailors know they were carrying the body of St Mark. There

was one man in another ship that joked, and said: Are you sure you have St

Mark? Maybe they gave you the

body of an Egyptian! Then the ship where the holy body was, turned

after him, and rudely boarded the ship of him that had said that

word, and broke one of the sides of the ship, and would never leave it in

peace till they had agreed that the body of St Mark was in the ship.

Thus

as they sailed fast before the wind, the air became dark and stormy, and

they did not know where they were. Then St Mark appeared to a monk who

was keeping watch on the body. He told him to lower their sails, for they

were near land, and he did so, and soon they landed at an island. And all

the natives they passed told them that they were happy that they carried

so noble a treasure as the body of St Mark, and prayed that they would

let them worship it. However, there was a sailor who did not believe that

it was the body of St. Mark. But the devil entered into him, and tormented

him so much so long that he could find on relief until he was brought to

the holy body. As soon as he accepted that it was the body of St Mark, the

wicked spirit departed, and from then he had great devotion to St Mark. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Why? As I have said elsewhere, politics and religion were tightly interwoven in Venice. Before St Mark arrived, the patron saint had been St Theodore of Amasea, definitely a B-list saint, and envious eyes were cast in the direction of Rome which could boast St Peter and St Paul. Even their maritime rival Amalfi had the relics of St Andrew. To have the relics of an important evangelist such as St. Mark hugely raised the status of the city. It would seem, though, that Buono and Rustico rather carelessly left St. Mark's head behind; The Coptic Church claims to have that in Saint Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in Alexandria. |

|

|

What happened next And so St Mark's basilica was built to house the remains. Unfortunately, two hundred years later, the unthinkable happened: the authorities forgot where they had put them. Various excuses have emerged, all rather contradictory; there had been a fire, there was building work at the basilica, the people who knew the location died suddenly without passing on the secret. All of Venice despaired, but St Mark himself came to the rescue; his arm suddenly appeared from a pillar, no doubt accompanied by a shout of 'I'm over here!' The remains were reinterred in the crypt in 1094, but the regular flooding meant that this was no place for something so precious, and in 1811 they were moved to their present location in a sarcophagus under the high altar. According to accounts of the time, his head was included. |

|

|

|

|

|

An aside: fragrant corpses The Golden Legend's strange tale of the sweet odour of the exhumed body is a myth that has been attached to many famous corpses. The same story has been told of the remains of St Teresa of Avila, even of Mohammed. Nearer to home, a similar sweet smell came from the head of James IV of Scotland, finally laid to rest at the rather unromantic sounding location of St Michael, Wood Street, London: Workmen, for their foolish pleasure, hewed off his head; and Launcelot Young, Master Glazier to her Majesty, feeling a sweet savour to come from thence, and seeing the same dried from all moisture, and yet the form remaining, with the hair of the head and beard red, brought it to London to his house in Wood Street, where for a time he kept it for the sweetness. John Stow, Survey of London, 1598. |

|