|

So what are

they?

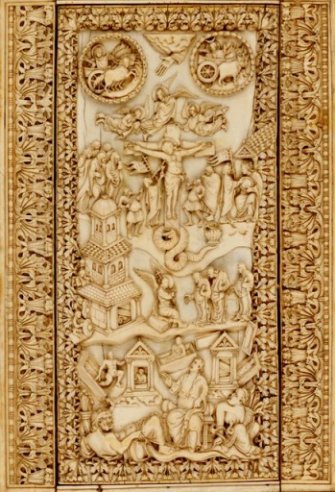

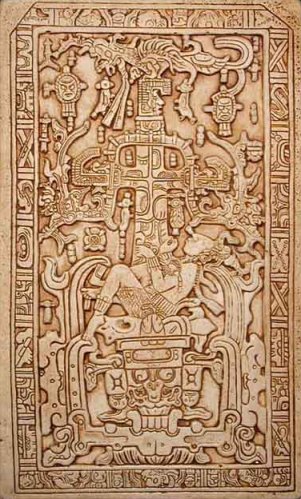

On the left above is the ivory cover from the

Pericopes of Henry II, an illuminated manuscript dating from c 1002. On

the right is the lid of the sarcophagus of Mayan King K'inich Janaab

Pakal I, who died in 683. The manuscript was produced at the Abbey of

Reichenau, in southern Germany. The sarcophagus was discovered in 1952

at the Mayan city of Palenque, in Southern Mexico.

The sarcophagus

lid.

K'inich Janaab Pakal I was the king of the Mayan city-state of Palenque, located

now in Southern Mexico. His long reign lasted from 615 – 683. His tomb

was discovered in 1952.

The complex iconography of the

lid of the sarcophagus has kept historians busy since it was discovered.

Pakal lies, infant-like, at the base of a stylised cruciform

tree.

Beneath him is the head of a serpent, sometimes interpreted as a skull.

Above the tree is a strange, supernatural bird. Around the top edge are

cosmological symbols of the sun, the moon, and stars; the celestial

realm.

The position of the king signifies resurrection

or rebirth, a return from the kingdom of the dead represented by the

gaping jaws of the snake. Pakal is shown as the maize god, the god of

the agricultural cycle; he has been resurrected as a divinity,

responsible for the cycle of death and renewal. The tree, bejewelled and

with writhing snakes, is bursting into life.

The pericopes cover.

A pericope is nothing to do with

submarines! It is a gospel text specifically selected for a particular

service or feast day. The cover of these pericopes is one of the finest

examples of Carolingian ivory carving.

The main element is the Crucifixion scene.

Christ is seen slumped on a roughly-hewn cross

with arms like cut tree branches. Whether He is represented here as

alive or dead is a matter for debate.

He is

surrounded by figures familiar in

crucifixion

scenes: John, Stephaton, Longinus, the weeping women. The allegorical

figure of Ecclesia collects the blood of Christ in a chalice. The two

figures to the far right have led to much debate. Synagogia?

Personification of Jerusalem? No one is quite sure, though the disc one

of them holds is highly suggestive of a paten, another Eucharistic

symbol.

Above the Crucifixion scene are angels carrying

the instruments of the Passion. Above them are the symbols of the moon

and sun.

Below the cross is a writhing serpent,

personifying sin and death, and also the serpent in the Garden of Eden

which caused the downfall of the first Adam. Christ, the second Adam,

has vanquished it.

Below the Crucifixion scene are the women at the

tomb, representing the Resurrection. This is reinforced with scene below

showing the resurrection of saints, as described in the Gospel of

Matthew:

‘And the graves were opened; and many bodies of

the saints which slept arose, And came out of the graves after his

resurrection, and went into the holy city, and appeared unto many.’

(Chapter

27 v 52-53)

At the base of the ivory are three very

strange figures. A semi-naked man with horns sprawls at the left,

pouring water from a vessel. This is Oceanus, a personification of the

ocean. To the left a bare-breasted woman suckles a snake. This is Terra,

the personification of the land. The central figure is another

bare-breasted woman. It is not clear what she represents, though

the best guess seems to be the temple. This theory is based on a

reference in a poem by the fifth-century poet Coelius Sedulius, familiar

to the Carolingians:

‘That marvellous temple,

filled with ancient religion, groaned like a sad foster-child and wept

for her own creator, as she beheld the roofs of the great temple fall.

When the temple veil rent she immediately showed her bare breast to all,

signifying that the secret things that were in were now to be revealed

to the Gentiles and all future people of faith.’

A comparison.

Clearly, any hint of Mayan culture was

unknown in Europe in the Middle Ages, and the two lifestyles and belief

systems were totally different. The Mayans had many gods. And yet it is

intriguing how many elements the two images have in common. Both of them

relate the wider universe – the sun, the stars, the sea and the earth –

to the narrative. Both images show the snake as personifying death and

evil, and the tree as the embodiment of new life and fertility: the tree

of life that ‘blossomed again in the resurrection so as to become the

beauty of all’. (Bonaventure,

The Tree of Life.) Above all, the central message

of both images is the same – the resurrection of a human into a god to

bring about rebirth and renewal.

Even here there are significant differences. As far as we know, Pakal

died a natural death, while Christ was sacrificed to bring that renewal

about. Of course, sacrifice was important in Mayan culture, and a bloody

business it was too. Let’s not forget, though, the importance of blood

in Christian theology; look again at Ecclesia in the pericope cover.

So what conclusions can be drawn? What the two images bring to

the fore are those nagging archetypes that just won’t go away. However

distant and unrelated cultures are, that collective unconscious keeps

throwing up those symbols. Individual minds can then interpret them and

use them in their own distinct way.

|