|

Conspiracy theories and the Ghent Altarpiece |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

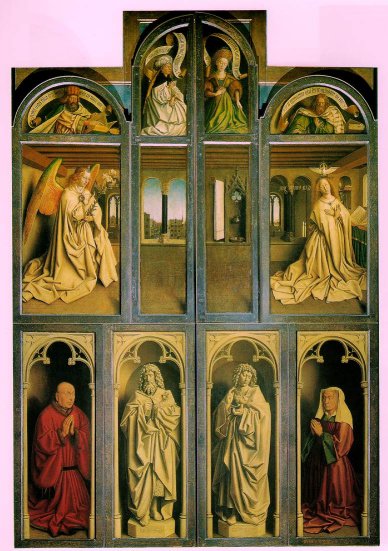

So let's have a look at it and consider one or two common sense, if less dramatic ideas. Yes, it's certainly full of strange images not often met with in other paintings. Conspiracy merchants might do well to consult Dhanens rather than Hollywood, however. She makes a strong case for the iconography of the picture to be based on the theology of the twelfth-century theologian Rupert of Deutz, who came from Liege, not that far from Ghent. He wrote extensively (and I mean extensively) on the Gospel of John, and it is this gospel, with its mention of the Lamb of God, along with the Book of Revelation (also supposedly by John) that is at the heart of the iconography of this picture. The altarpiece is not a static picture, but a journey. With the shutters closed, we are presented with images of the incarnation. At the top are the prophets and sibyls that foretold the coming of Christ. In the centre is the Annunciation. Below are the donors, and between them the two key figures in the story: John the Baptist, who came up with the phrase Lamb of God, and John the Evangelist. When the panels are opened, the Evangelist's story reaches its conclusion, with images of redemption based on the Book of Revelation. One point often missed by the conspiracy theorists is the amount of didactic text included on the altarpiece, explaining the meaning of the various panels. Perhaps the most important are these words from the mass: Ecce Agnus Dei qui tollit peccata mundi, 'Behold the Lamb of God which taketh away the sins of the World'. The main scene shows the Lamb of God surrounded by hosts of people: prophets, patriarchs, saints, martyrs, precursors of Christ, churchmen, apostles, confessors. The side panels show hermits, pilgrims, judges and knights. All of the these represent 'the great multitude, which no man could number' (Revelation 8. 9) Around the Lamb are angels, with items connected with the crucifixion: the scourge, the nails, and so on. In front of it is the fountain of life, and this is at the heart of the interpretation of the painting. Again, the picture has helpful text, this time around the fountain: Hic est fons Aque vite procedens de sede Dei +Agni. 'This is the fountain of the water of life proceeding out of the throne of God and the Lamb'. Rupert of Deutz had particular views on the Eucharist: his ideas, known as impanation (the body of Christ embodied in bread and wine) were not unlike transubstantiation, but sufficiently different to be regarded as heretical. (If you want to follow this us up, there's a very brief article on impanation on Wikipedia, which includes a useful link to the Catholic encyclopaedia. It's pretty arcane stuff.) Perhaps better than reading this, imagine the scene at the Eucharist. The priest stands before the painting. He holds up the chalice; the blood flows from the altar to the fountain of life, and, from the communicant's viewpoint, the water from the fountain pours straight into the chalice. It's not just a picture, it's an active participant in the drama of the Eucharist. These ideas would almost certainly have been supplied to the van Eycks by a member of clergy. It really wasn't the job of a painter to come up with the detailed content; they painted to order, and slipping in their own heresies was definitely not encouraged. But why the Lamb? As we've seen, its portrayal is unusual. Doesn't this raise questions? Well, here's an idea. The donor of the painting was Joos Vijd, a wealthy financier, who made his fortune from wool. In the Middle Ages Ghent was the centre of the wool trade in Europe. For this reason a lamb, and by association John the Baptist, was an important symbol of the city, as shown here on the medieval great seal of Ghent (left). The current coat of arms (right), from the town's website, shows the lion of Judah, that strange combination of lion and lamb described in Revelation chapter 5. |

|

|

|

|

| So, when the priest raised that chalice before the great altarpiece, immediately behind it was the Lamb - attribute of John the Baptist, patron of the chapel, and symbol not only of Christ and the Eucharist, but also of the donor and the city itself. Complex theology, and maybe just a little local self-congratulation, merge to create one of the greatest paintings in the world. So - mysteries solved? Not quite. Look again at the figure in the Papal tiara immediately above the Lamb of God. Here's an enlarged version. Who is it? |

|

|

|

|

|

The text ought to sort this out for us. It begins Hic est Deus

potentissimus propter divinam maiestatem. 'This is God, the

Almighty by reason of his divine majesty'. But there is a problem.

On either side of this figure are images of the Virgin Mary and John the

Baptist. In all ways but one this is a familiar Last Judgement scene,

with Mary and John acting as intercessors. But for that to be right the

judgement figure should be Christ, not God. When we look behind the

figure there is a tapestry, and on the tapestry are woven grapes and

pelicans - symbols of Christ. Christ seems to be the most likely candidate - and yet - notice something about the hand? No 'holy wounds' caused by the nails at the crucifixion. A quick check through other versions of the Last Judgement show that, for the most part, these were included. |

|

|

|

|

|

Was this ambiguity deliberate? Again, the text on the image should help.

The text on the robe includes 'King of Kings and Lord of Lords' from

Revelation. This text was amplified in the writings of Rupert of Deutz: |

|

| 1 Elisabeth Dhanens Van Eyck: The Ghent Altarpiece. Art in context series, Viking Press NY 1973 2 From the writings of Rupert of Deutz collected in Patrologia Latina by Jacques Paul Migne published between 1844 and 1855. |

|