|

The New Testament |

|

| The Gospel of John and the Book of Revelation are at the heart of any consideration of the Lamb of God. The events of the Passion are prefigured in the words of John the Baptist: Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world. John 1. 29. In the synoptic gospels, the Last Supper is eaten as a Passover feast, for which lambs have been sacrificed. John's gospel moves the events a day earlier, so that the Last Supper happens before the Passover and the crucifixion coincides with it - effectively, Jesus becomes the Paschal Lamb, the Passover sacrifice. Paintings of the Last Supper have provided interesting material for food historians and for celebrity chefs looking for bizarre ideas to outdo their rivals. Of course, the most important ingredients are the bread and wine, and in focussing on these, some Last Suppers look a little meagre, and the apostles might have headed home rather hungry. Should a Paschal Lamb be there? Paintings based on the synoptic gospels might well include one, but if artists took their inspiration from John it would be correct not to. In Jacopo Bassano's last supper the Paschal Lamb has been eaten, and just its head remains. The happy dog looks as if has had his share. |

|

|

|

|

| Crespi's last supper looks much more inviting, with a roast lamb and plenty of fish - appropriate, of course, for the apostles, who were fishermen. The fish is a powerful Christian symbol. The round things (top left in the detail) look interesting - can any cooks guess what they might be? Slices through an orange? |

|

|

|

|

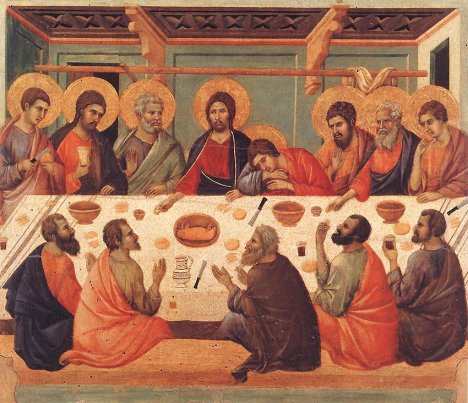

| Duccio's Paschal Lamb is a rather odd looking creature, more like one entirely unsuitable for a Jewish Passover. | |

|

|

|

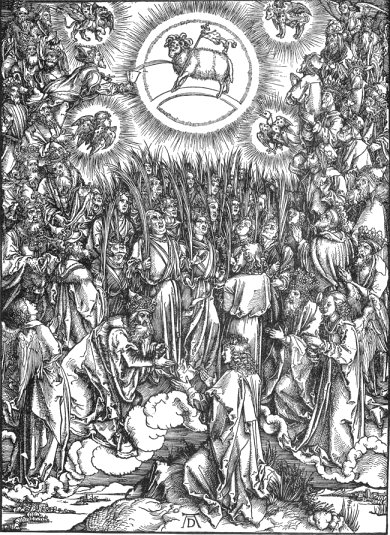

| The Book

of Revelation has been a happy hunting ground for scholars from the very

earliest times, and, inevitably, no-one agrees on what it means. What

are we to make of the book's extraordinary imagery, with its Lion of

Judah, half lion, half lamb, with seven eyes and seven horns?

Saint Augustine offers what is probably

still the best interpretation: |

|

|

|

|

| The image of the lion of Judah is a study in itself.

Christian versions such as Durer's tend to be more lamb-like, other

faiths more lion-like. The blood and cup in Durer's image stress the

sacrificial element. The older version of the Ethiopian flag (below) shows a lion. Although the flag has now been replaced with something rather blander, this version is still popular with Rastafarians. |

|

|

|

|