|

In

the wilderness - temptation and penitence |

|

|

Jerome left his friend Evagrius in Antioch

around 374, and settled as a hermit in the Syrian desert for a period of

around two to three years. It is interesting to contrast the image of his

life there presented in paintings (and in Jerome's own later writings)

with what we know of the reality of his experience, as described by J N D

Kelly.* |

|

|

|

|

| Titian's picture (left) is fairly typical of images of Jerome in the desert. Bosch's picture is typically over the top; even the trunk of a tree looks like a giant fish ready to devour him. | |

|

|

|

|

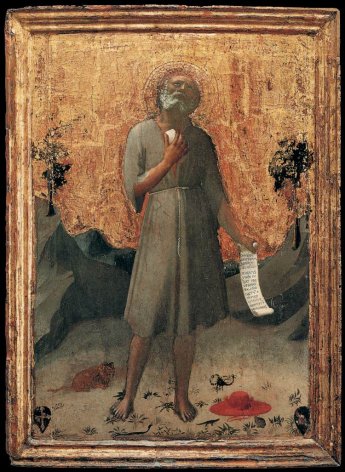

Fra Angelico (below left) shows Jerome beating himself with a rock in penitence. Around him are the scorpions mentioned in the extract from the letter to Eustochium quoted below. Jacopo del Sellaio's wonderful picture (below right) illustrates the usual iconography of the penitential Jerome: a skull, a crucifix, and once again the rock. The other characters in the picture are St Mary of Egypt (right) and John the Baptist praying to a young Christ. Both John and Mary spent part of their lives in the wilderness. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

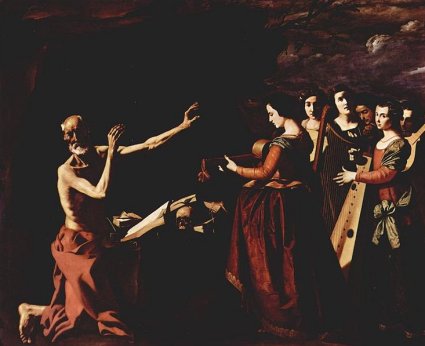

So what was Jerome being penitential about? His

letter to Eustochium continues: Now, although in my fear of hell I had consigned myself to this prison, where I had no companions but scorpions and wild beasts, I often found myself amid bevies of girls. My face was pale and my frame chilled with fasting; yet my mind was burning with desire, and the fires of lust kept bubbling up before me when my flesh was as good as dead. Helpless, I cast myself at the feet of Jesus, I watered them with my tears, I wiped them with my hair: and then I subdued my rebellious body with weeks of abstinence. I do not blush to avow my abject misery; rather I lament that I am not now what once I was. I remember how I often cried aloud all night till the break of day and ceased not from beating my breast till tranquillity returned at the chiding of the Lord. I used to dread my very cell as though it knew my thoughts; and, stern and angry with myself, I used to make my way alone into the desert. Wherever I saw hollow valleys, craggy mountains, steep cliffs, there I made my oratory, there the house of correction for my unhappy flesh. There, also - the Lord Himself is my witness - when I had shed copious tears and had strained my eyes towards heaven, I sometimes felt myself among angelic hosts, and for joy and gladness sang: "because of the savour of thy good ointments we will run after thee." This is all very confessional, and is illustrated by these pictures by Zurbaran and Vasari. Zurbaran shows the bevies of girls; all very respectable looking, at least in this picture. The Vasari picture brought forth stinging criticism from Anna Jameson (Sacred and Legendary Art). She did not approve of classical cupids in a religious picture: 'an offensive instance of the extent to which, in the sixteenth century, classical ideas had mingled with and depraved Christian art.' But was she right? Jerome relates that love of classical (i.e. pagan) authors such as Cicero was one of his greatest weaknesses. Appropriate, then, that he should be threatened by a pagan god of love. |

|

|

|

|

|

Jerome's time in the desert ended rather unsatisfactorily. It appears that he did not get on well with the local hermit community; getting on well with the neighbours was never one of Jerome's strong points. He also became embroiled in all the 'isms and schisms' that beset the church at the time, including choosing between local competing bishops. He eventually returned to stay with Evagrius in Antioch. The fresco by Benozzo Gozzoli below is entitled 'Jerome departs from Antioch'. I'm not entirely sure whether he is departing for the desert or for Rome (I'd guess the latter), but what is interesting is the other character, whom I assume to be the long-suffering Evagrius. Was he pleased to see the back of Jerome? either way, he is equally deserving of a halo. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|