|

Circumcision is a Jewish

covenant laid down in the book of Genesis:

And God said unto Abraham, Thou shalt keep my covenant therefore, thou,

and thy seed after thee in their generations. This is my covenant, which

ye shall keep, between me and you and thy seed after thee; Every man child

among you shall be circumcised. And ye shall circumcise the flesh of your

foreskin; and it shall be a token of the covenant betwixt me and you. And

he that is eight days old shall be circumcised among you, every man child

in your generations, he that is born in the house, or bought with money of

any stranger, which is not of thy seed. He that is born in thy house, and

he that is bought with thy money, must needs be circumcised: and my

covenant shall be in your flesh for an everlasting covenant. And the

uncircumcised man child whose flesh of his foreskin is not circumcised,

that soul shall be cut off from his people; he hath broken my covenant.

(Chapter 17 v 9 - 14)

In the earliest days Christianity could be viewed as a Jewish sect.

Inevitably, then, circumcision was something of a problem for Gentile

converts, many of whom were (understandably) not very keen on the idea.

Thus St. Paul and others developed a Christian theology of circumcision,

which is why this ostensibly Jewish ritual continued to preoccupy

theologians and artists over the centuries. Simply put, circumcision,

traditionally the ceremony at which a child was named, has

been replaced by baptism. Christians did not need to be circumcised

because Christ had already done it for them. This makes the Circumcision a

foreshadowing of the Crucifixion - a shedding of blood to redeem the

sins of man. Thus it was an important event in the life of Christ

and demanded attention from artists.

This is very simply put, and there is far more in Leo Steinberg's

important (I'm trying to avoid the word seminal) book The

Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion.

I'll be referring to it later on when I discuss Renaissance images of the

Christ child. It's a book that all those with an interest in

religious art should read.

Steinberg mentions examples of the use of the image in later

Northern art that are anti-Semitic, though this is certainly not

mainstream.

|

|

Mantegna: Uffizi, Florence. Note the Old Testament

references to Abraham and Moses in the lunettes above.

|

|

Barent Fabritus: Private collection.

Fabritus takes an Old Testamant view with a turtledove and a lamb (though

it seems there are two lambs.) Fine, but of course these items relate to

the Presentation at the Temple, not the Circumcision. I'm not sure what is

in the basket - bread? (There's a larger version of this picture on the

Web Gallery of Art website at wga.hu. )

|

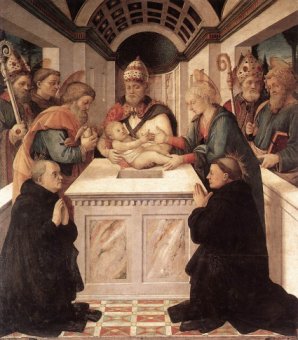

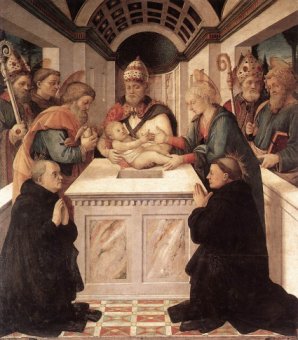

Fra Filippo Lippi: Santo Spirito, Prato.

Various saints, bishops and donors have turned up to watch. The bishops

are probably saints too, but combining mitres and haloes would defeat even

Fra Filippo. Joseph has brought the pair or doves along just in

case.

|

The naked Christ Child

Slightly off-thread perhaps, but here are two thoughts raised by

reading the Steinberg book mentioned above.

1. Medieval paintings showed the Christ child clothed.

Increasingly, in Renaissance art He was shown naked, sometimes with the

genitals prominently displayed. Sometimes a viewer's attention was drawn to

the genitals by other figures in the painting. What's going on?

A couple of years ago my wife and I visited the revamped Museo

Diocesano in Parma. One painting, by, I think, an unknown artist caught our

eye. It showed a standard Virgin and child with the Child standing on the

Virgin's knee. The strange thing was that the Virgin, with a rather silly

grin on her face, was pointing directly at the Christ Child's genitals. (I

would have sneaked a photo if the CCTV camera hadn't been pointing directly

at me.)

It's a object lesson on how preconceptions and modern day culture

distort our view of the past. I'm sure that many modern viewers would see it

as offensive. I just thought it odd, but I hadn't read Steinberg at that

point.

The nature of Christ - human, divine, one or the other, or both, and if

both how did that work - has obsessed theologians over the centuries, right

through to the modern age when most people have given up worrying about it.

Until the modern age, Christ's genitals were not thought of as something rude needing covering up,

but as - literally - a sign of a divine being made man - the human aspect of

Christ. The covering-up in medieval images could be seen as a denial of

Christ's humanity.

It also reflects the story of Adam and Eve, who before the fall 'were

both naked, the man and his wife, and were not ashamed,' (Genesis 2)

but afterwards were clothed in 'coats of skins'. Christ, as the Second Adam,

has taken away the shame.

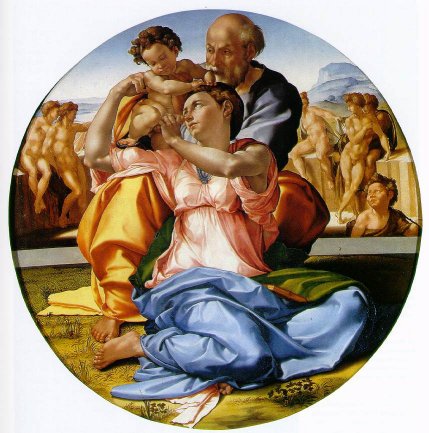

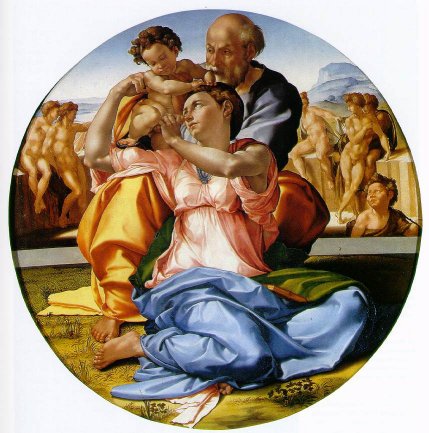

This issue has been discussed by William Wallace in his lecture on the Doni

tondo in the Teaching Company lectures on Michelangelo. (Highly recommended,

by the way.) His

interpretation supports Steinberg's ideas.

|

|

Uffizi, Florence

|

|

2. Christ was circumcised at the age

of eight days. Yet no Renaissance painting shows the Christ child, or any

other figure for that matter, as being circumcised. (The example that is

most often mentioned is Michelangelo's David.) Why not?

Some people have suggested that there were a lack of models,

but Steinberg rejects this - there were many circumcised Muslim working as

slaves in Italy at the time. He feels it is more to do with an artistic

striving for perfection; historical accuracy was not a concern that gave

Renaissance artists sleepless nights.

|

|

Raphael: Madonna del Cardalino

Uffizi, Florence

|

In Raphael's painting the Christ Child,

the second Adam, is uncovered, but the young John the Baptist remains

covered with his usual animal skin. A sensible course of action now would be

to post a close-up of the relevant part of Christ to prove my point about circumcision.

So why don't I feel comfortable doing this? A modern sensitivity?

You can blow up the image on the WGA website.

|

|

The

Purification of the Virgin and the Presentation of Christ at the Temple

|

|

Home page

Life of the Virgin Index

|